"The things that make us happy are simple things like chatting to our mates, hanging out with our family, going for a walk with a dog, watching the birds tweet in the garden, walking up a hill and looking at the view... The things I love most that I cherish most are mostly things that either I've had for a very long time or I have inherited from my dad or my grandparents... those things were the things that are most special to me and they're most special because they have inherited a life and a spirit."

There's a moment in Patrick Grant's recent interview where he draws a line that cuts straight to the heart of modern consumption. On one side: businesses that create value for everyone in their ecosystem - farmers paid fairly, makers valued for their skills, customers cherishing products for decades. On the other: "valueless" enterprises where no one wins except shareholders, churning out AI-generated replicas of last year's garbage.

It's a distinction that extends far beyond fashion.

"Knowing the weaver and standing in the weaving shed and looking out over the macchair at the turquoise sea on the Isle of Harris makes you feel great when you wear that jacket... that stuff is the stuff that's going to not only make us feel happier but it's going to restore the health of the planet and deal with the inequalities that we're increasingly seeing."

Fashion vs. Quality Clothing

Here's Grant's radical proposition: what if we stopped chasing fashion and focused on making really good clothes? Not everything needs to be "on-trend." Some things can just be excellent at their job - a well-cut trouser, a perfectly weighted cardigan, a sock that simply works brilliantly.

He draws a sharp distinction between clothing (which we need) and fashion (which we might want but certainly don't need). Fashion manipulates us into buying more; clothing serves us.

What's particularly troubling is how government policy reinforces this hierarchy. Grant points out that successive administrations will spend £100 million supporting an electric car battery factory that goes nowhere, but won't invest in people making mattresses, chairs, or textiles - things we actually know how to make well.

The assumption that "advanced manufacturing" only applies to high-tech products shows a fundamental misunderstanding. "You can't make pencils in the modern world if you aren't a really good modern manufacturer," Grant argues. Simple products still require sophisticated manufacturing.

"Some brands spend more money advertising their product than they do making it. We make the best quality clothing we can make and we let the quality speak for itself."

The Economics of Care

Grant grew up in a house filled with quality - furniture bought once and kept for generations, cutlery inherited from grandparents, clothes that were mended rather than discarded. His grandmother darned stockings. His family fixed things. Quality wasn't a luxury; it was simply how life worked.

That world feels revolutionary now.

This shift back to fundamentals isn't theoretical. I've seen brands rediscover their foundations - focusing on what they've always done best rather than chasing every trend. When you lead merchandising for heritage outerwear and crafted pieces, you learn that some categories transcend fashion entirely. A perfectly engineered trench coat or quilted jacket isn't about this season's mood board; it's about solving problems elegantly for decades.

Community Clothing makes a radical proposition: what if we focused on making really good things instead of chasing trends? Not everything needs to be "on-trend." Some things can just be excellent at their job - a well-cut trouser, a perfectly weighted cardigan, a sock that simply works brilliantly.

The question isn't whether we can afford quality. It's whether we can afford to keep supporting systems that create value for virtually no one except people who already have billions tucked away.

But here's the challenge Grant identifies: even if we wanted to rebuild this system, where would we find the people to do it? His business could theoretically create 100,000 jobs if just 5% of UK clothing purchases were made domestically. But those skills have vanished. We've convinced an entire generation that making things isn't a good career, while removing hands-on learning from schools - no more pottery, woodwork, or textiles.

"We've broken all the family bonds where children would follow parents into manufacturing careers," Grant observes. Without understanding how things are made, we can't even recognize quality when we see it.

Every purchase is a vote for the kind of world we want to support.

"We can choose to do really good things with the money that we spend. We can choose for it to go into the pockets of people that we'd like it to go into the pockets of, or we can carry on doing things the easy way and just give all of our money to a load of billionaire global oligarchs who don't need any more of it."

What's the oldest thing you own that still brings you joy?

Read More

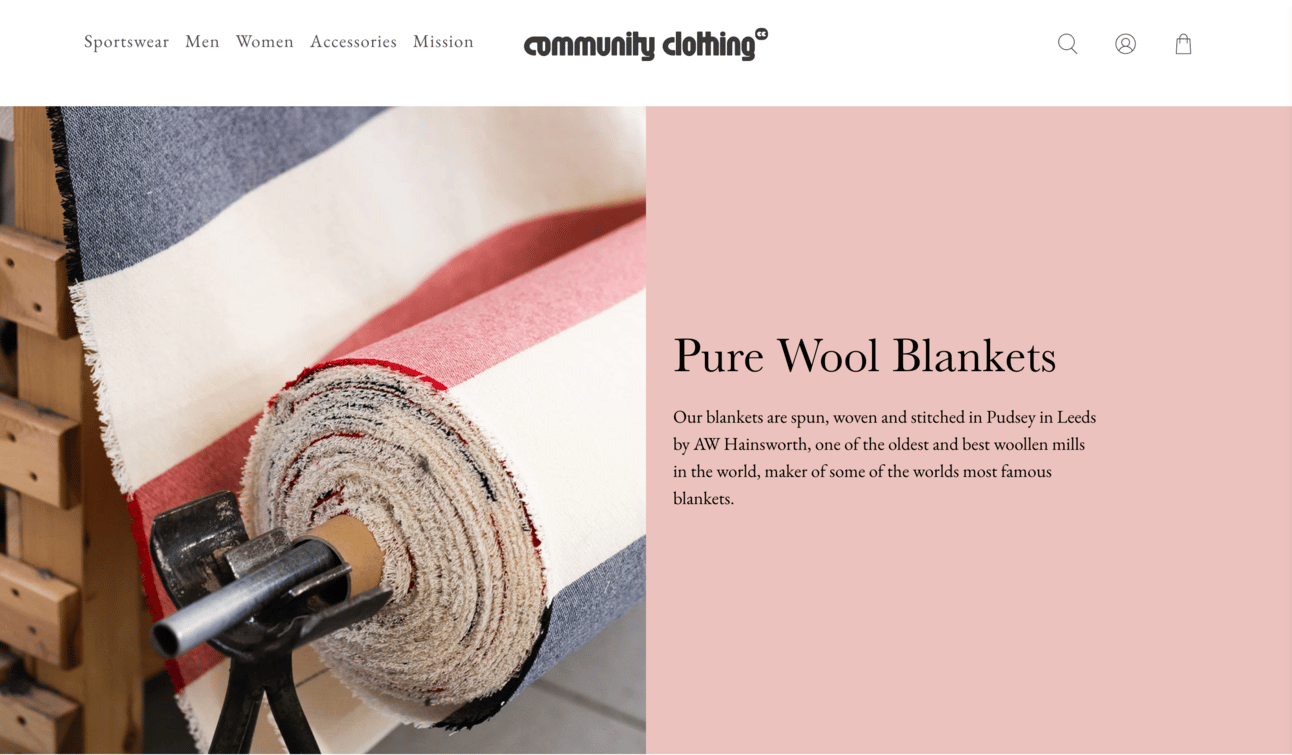

Community Clothing in Practice: See how Patrick Grant's philosophy translates to real business impact - 140,000+ hours of skilled work created, transparent pricing, and manufacturing within 100 miles of Birmingham for the Commonwealth Games uniforms.

The Full Interview: Listen to Grant's complete conversation about happiness, heritage, and the future of British manufacturing. [Link to original podcast]